- Home

- Works in Exhibitions

- Fridel Dethleffs-Edelmann

- Ursula Dethleffs

- Treasures from the Collection

- Collection of art

- Watercolor

- Tapestry

- Collage

- Gouache

- Reverse glass painting

- Glass church window

- Glass Mosaic

- Ceramic Plate

- Ceramic Picture

- Ceramic Relief

- Ceramic Sculpture

- Mixed media

- Object Art Relief

- Object Art Sculpture

- Oil Paintings

- Repro Lithography

- Repro Glass Lithography

- Repro Woodcut

- Repro Linocut

- Repro Monotype Printing

- Repro Etching

- Tempera

- Drawing Brush

- Drawing Brush Repro

- Drawing Ink and Pen

- Drawing Crayon

- Drawing pencil and crayon

- Exhibition by Period

- FDE: Selfportraits

- Introduction to the work of Ursula Dethleffs

- The collage as a total artwork

- Biography

- Dethleffs Gallery

einzigartig

Fridel Dethleffs-Edelmann

Ursula Dethleffs

Fridel Dethleffs-Edelmann

Ursula Dethleffs

Between Good Friday and Pentecost - with works by Ursula Dethleffs

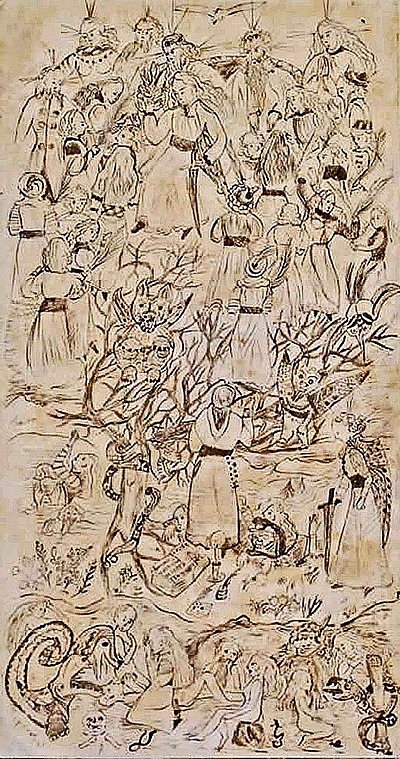

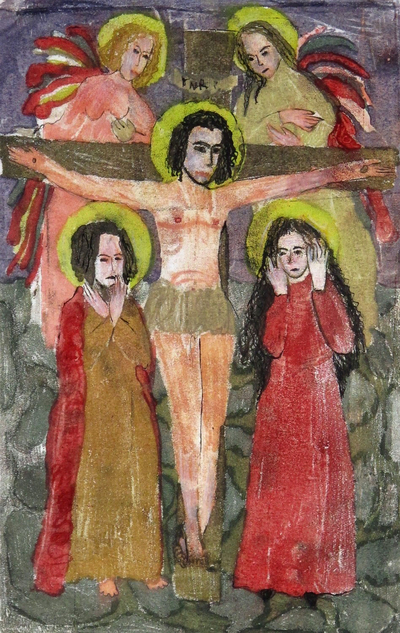

Color pencil drawing, 1945 at the age of 12

What a question? Sure - the corona epidemic has been an exam for everyone since April 2020. But that doesn't mean we can forget that in 1945 many peoples were still infinitely worse off than they are today: Who wasn't desperate back then? With all the dead, abused, with the often total destruction? It is unbelievable that the peoples have found a way out of this desperation. We can remember this especially in the time between Good Friday and Pentecost. The works of Ursula Dethleffs from this desperate time can accompany us.

At that time Germany was almost completely destroyed. Germany surrendered on May 8, 1945. It was occupied by soldiers from the four victorious powers. In Germany wandered around: children, women, soldiers, war invalids, liberated, prisoners from concentration camps, German refugees - and even more desperate people. They all looked for food, for a roof over their heads, for relatives, for doctors, hospitals, for help in order not to starve to death. The "Third Reich" had lost its total war, and Arist Dethleffs had been drafted as a soldier five years earlier, probably because he had not believed in the final victory (1940)

After saying goodbye, Fridel, her mother Luise Edelmann and Ursula were alone. Fridel's mother took over the little stable with one cow and hens. Fridel was responsible for the family and the house, while the factory for whips and ski poles continued to be run by Albert Derhleffs and his brother. The caravan production had been shut down because of the war. Mrs. Eisleb was the good spirit in the household.

Since the war had not even noticed Isny, which was hidden in the Allgäu, the Isny people were still fine if you forget the worries women had about the soldiers.

Fridel, Gogge and Frau Eisleb were mainly busy keeping Ursula away from anything that could have affected her. In addition to her work, Fridel could not do without painting. Sometimes Ursula was allowed into the studio. She was then usually allowed to copy a picture from her mother's art books. Today she would have started with abstraction. In the art books back then, people, animals and trees were still drawn as they are, only with Ursula's younger dish it went haywire - like with Hieronymua Bosch.

Here Arist with Ursula - they are happy that the family is together again. Arist and his family were lucky. He was released home as a soldier in 1945: healthy and without war injuries. At the end of World War II. on May 8, 1945, Ursula Dethleffs was 12 years old. Back then, the day of peace was a day between Good Friday and Pentecost. Ursula did not have to experience a night of bombing herself.

She had been brought up strictly by her mother. Ursula's grandmother - affectionately called "Gogge" in the Baden translation for grandma - looked stern, but Ursula was able to wrap her around her finger. Just like her "Vattle".

The family Edelmann came from Ottersweier. Luise Edelmann's father was a farmer who had grown

tobacco. Luise married the innkeeper Jacob Edelmann, who ran the “Zur Krone” inn in Hagsfeld near Karlsruhe. Hard work was a matter of course for both spouses. In addition to working as an innkeeper, he was also allowed to distill schnapps. After the death of her husband, Luise Edelmann moved back to Ottersweier.

Augustinermuseum Freiburg

Arist Dethleffs and Fridel Edelmann celebrated their wedding in Karlsruhe in 1931. Then they moved to Ottersweier to live with Luise Edelmann's mother-in-law. She lived there alone in her parents' house. She was happy that the young family moved in with her; an apartment was available there for the two of them. Ursula was born there in 1933. After five years, Arist moved to Isny with his three wives: there the new Dethleffs house on the outskirts of Isny had been completed. To the great delight of Ursula, her Gogge moved in.

Ursula received exceptional support as an artist from two women. Astonishingly, her grandmother was the most important woman for the first 24 years. It was only after the grandmother's death in 1957 that her mother became Ursula's favorite and most important caregiver for 25 years.

That was initially due to Fridel: As a mother, she was happy about her daughter. She was no less happy that her mother was so touchingly worried about her granddaughter. Because in this way she could devote herself to her art - without any feeling of guilt. In addition, the daughter often sat in the studio and learned a lot of techniques that are important in art.

But it was even more down to the Gogge: the grandmother had worked hard as a farmer's daughter even in her youth. For many years, her job as a hostess was even more challenging for her. She didn't have any free time for her own personality. She wanted to spare her daughter this hard life. That is why the innkeeper and his wife agreed when they allowed Fridel to follow her wish to become an artist. Art was nothing strange to the two of them. For her, art was part of life.

The factory owner's son Arist could not have wished for a better mother-in-law.

Fridel's painting shows her mother as a strict woman with a high forehead and a sharp mouth. She could have been a pietist: for whom nothing is more important than the love of God; if success is worked hard, then everything is pleasing to God. Pietists know their way around the Bible very well.

Ursula experiences her loving side, which cannot be derived from the painting, who cuddles close to her Gogge every day in the painting by Fridel Dethleffs-Edelmann. At the same time, the grandmother fulfills the wish of her painting daughter: as a model, she should please hold still and sit up straight. Since Ursula can seldom sit still, the grandmother looks over her. She holds the book with one hand. Ursula keeps her mouth closed for the painting mother, although she would much rather read aloud. So the two sit on the armchair and everyone suspects that the two are one heart and one soul.

The Gogge knew everything that is in the Bible. Ursula listened with fascination as Mary gave birth to Jesus in the stable at Christmas and that he was lying in a manger because they were poor. She knew the Star of Bethlehem and the Three Kings. She could not understand the crucifixion of Jeses. But his resurrection to heaven to his Father comforted them.

Without her Gogge, Ursula would not have been so closely connected to Christianity: her grandmother was the source of her faith.

Her mother, as a painter, always took the time to introduce Ursula to the works of Dürer, Rembrandt and Picasso from her large art library. Ursula never went to university. To do this, her mother introduced her to the history of classical art: through books, through visiting exhibitions and museums on her many travels. In addition, she “went to school” with many important artists from her mother's circle of friends - to name just three: Max Ackermann, HAP Grishaber, Sepp Mahler. The most important teacher for Ursula was always her mother.

The biblical time from Easter to Pentecost has moved Ursula again and again. The works that we are going to present to you here were created between 1946 and 1989.

In the beginning Ursula Dethleffs used the pencil for this, later the colored language of behind-glass art. During her training with her mother and until the end of her own life, Ursula repeatedly learned new art techniques. (You will get to know a part of it here.) At the end of her life, Ursula then opened up the encrypted works of object art. Few artists were so comprehensive and at the same time so strong in their impact.

1946: Christ enters Jerusalem / Christ before Pilate

Ursula had been painting behind glass pictures when she was eight, i.e. since 1941. Ursula was still in training at that time - but the pictures were already being admired in exhibitions at that time. The two reverse glass pictures shown here were painted by the thirteen-year-old in 1946. Both based on their grandmother's biblical stories. Since behind glass pictures are painted the wrong way round on the back of the glass plate, this work was an important step for Ursula. Ursula learned the graphic division of the glass surface and the feeling for the harmony of the colors from her mother in the “stroller”.

How early Ursula worked with her many and very different techniques can be seen from a chapter on this homepage:

The many pages of the chapter are arranged according to technology and year:

Link to: Exhibitions by Period.

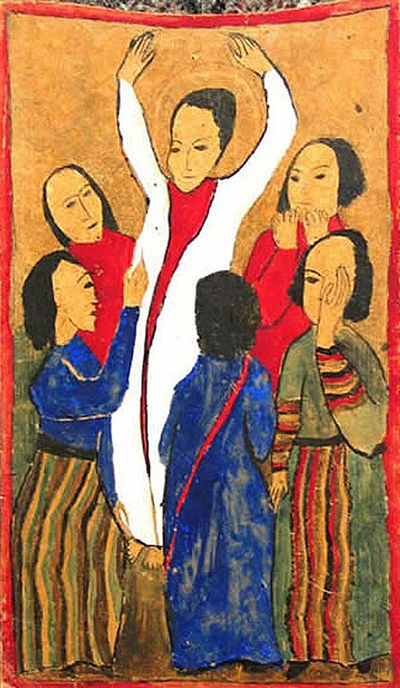

1948: Christ under the cross / resurrection / at the wayside cross

In the first two works with tempera colors, Ursula mixed the colors herself, as in the watercolors: the color variation in the warm tones was unlimited. Tempera is mixed with water-oil and with gouache with a water emulsion without oil.

In front of a dome, Christ sank to the ground under the weight of the cross. On the right he is mourned by a woman, on the left by the warrior who will later hold the sponge dipped in vinegar to his lips.

The next picture shows the resurrection: Christ floats up from the circle of women in a white cloak over the red petticoat in the sky. The red is repeated on the women next to him. One of the three women in front is dressed entirely in dark blue, while the skirts of the other two with their vertical stripes underline the Ascension.

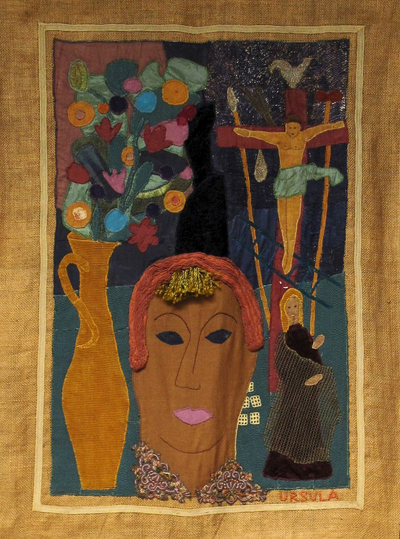

In the early years Ursula mostly sewed her tapestries - like here - on sackcloth.

That was obedient to the need. Because she would have loved to work with new fabrics.

That was too expensive for a Swabian factory owner's daughter long after the end of the war. She gathered the fabric appliqué from scraps of fabric or old textiles that she had requested from relatives and acquaintances.

At the very top right on the cross sits Peter's rooster: he had denied Jesus three times. Next to the cross, two lances protrude into the sky: with one of them Jesus became

a legionnaire handed a swan dipped in cheap wine to keep people from dying of thirst; the other lance stabbed Jesus through the fifth space between the ribs, into the pericardium and then into the heart. Mary of Magdala stands under the cross.

In the middle a large woman's head, probably Maria. On the left in the picture the large, slim vase with many colorful flowers, which are symbols of life and resurrection

1949: Christ's life from the cross to the resurrection / On the cross

Ursula Dethleffs was able to learn to work with clay from her family friend, master potter Bader, in Isny from 1944 onwards. He had met Ursula in her mother's studio. Ursula's continued enthusiasm for his pottery soon resulted in a father-daughter relationship. She painted her first bowl in 1944 and the last plate in 1970.

The ceramic bowl "Christ Life" with the seven stations is made of red clay. Ursula has painted “paint” in white on the bowl: Top right - The cross with the group of disciples; in the middle: Jesus on the cross with angels and the four women - his mother, her sister, Mary the wife of Clopas and Mary of the Magdala, etc.

Ursula was 16 years old when she painted the bowl. Even today there are girls whose energy and faith are strong enough for the task. Then there has to be a grandmother who knows her way around the Bible. If there is also a mother to help as an artist, the task could succeed. If…

No varnish was used because the large bowl (34 x 34 cm) would otherwise have reflected too much.

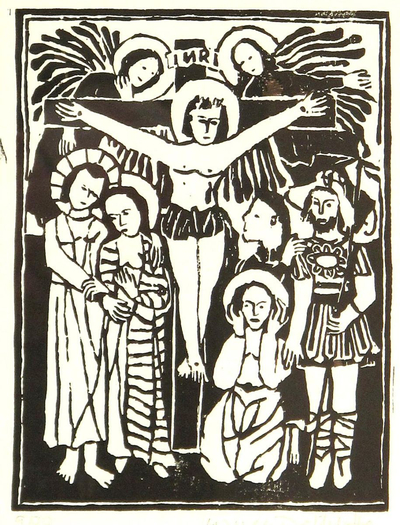

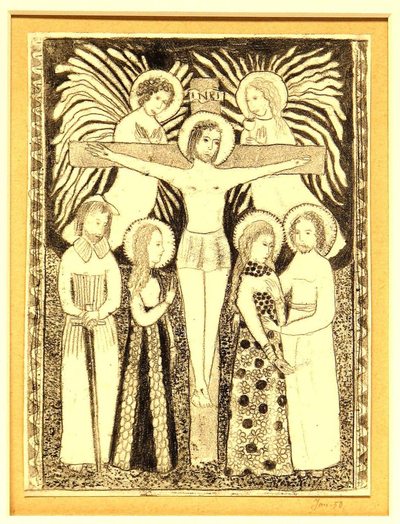

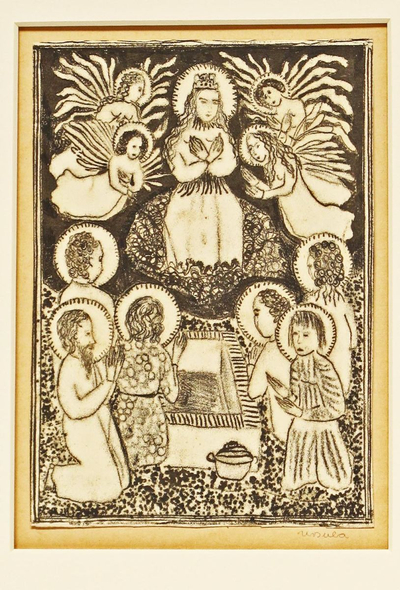

1949: Ceramics, Linocut, Glass lithograph

Many linocuts were made between 1949 and 1980. They were printed, signed and dated by Ursula herself in several editions. The linocut “Am Kreuz” dates from 1949. The artist varied the composition of the image several times.

The linocut on the left has internalized the tragedy of death on the cross. He literally lets you feel the silence of death. Nothing moves, everything is dead. The artist was 16 years old.

Ursula also designed the right glass lithograph "Am Kreuz" in 1949. In the case of multicolored glass lithographs, the different colors must be precisely delimited from one another. It can be assumed that Ursula consciously used the colors that run here; thus the contrast between the linocut and the glass lithograph becomes clear. It is no longer the rigid scene with death on the cross. Time no longer stands still. It is the time of the women on the cross until the ascension to heaven: the angels above the cross are ready to accompany Jesus to heaven.

Ursula Dethleffs learned glass lithography around 1944-45. The artist draws the design on Solenhofen stone slabs. A separate plate must be made for each color. After the chemical process, the panels are sequentially printed with the different colors. Ursula Dethleffs signed and dated the glass lithographs.

The glass litho "Am Kreuz" from the dance series "Marienleben" is consecrated to the suffering of Jesus. It is only printed in one color. This emphasizes the calm and tranquility of the dead Christ. The focus is on the cross with Jesus. The wings of the angels above and the noble clothes of the women next to the cross below add to the dignified atmosphere.

Ursula made many drawings with India ink as a child. Pen-and-ink drawings were only exhibited from 1945 onwards. The drawing of the Assumption of Mary reveals the almost naive piety of Ursula: above all in the touching beauty of the four angels who accompany Mary to heaven. In contrast, the six disciples represent the believing community in simple robes.

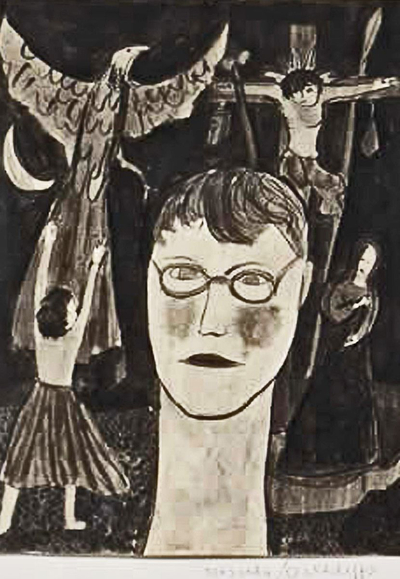

1954: Brush drawing

Ursula Dethleffs has drawn countless brush drawings since 1950, some of them true to detail, some as sketches. At first I hesitated to include this self-portrait here.

But it's typically Ursula. Sad and defenseless at the same time - like her mother. Certainly not the naive believer anymore. Your face dominates. The face of the crucified one is only hinted at. On the left a girl who wants to keep the Holy Spirit on earth, on his flight to God. On the right a woman who wants to run away, but does not force Jesus to be alone at his crucifixion.

This is not a scene from the Bible that her Gogge told. This is original Ursula Dethleffs. She places herself under the cross. All people are responsible for the crucifixion. Your sadness is great.

1955: The life of Jesus

The oversized head of Christ in the center almost exceeds the size of the color woodcut. On the cross Jesus had called: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” The six other calls have faded away. Jesus Christ died on the cross. He wears the crown of thorns as the king of the Jews. (His beard is there as a graphic counterbalance.)

The stoic head is framed by biblical stories:

top left - Jesus with his cross.

Opposite - Jesus with Peter in the Mount of Olives.

Bottom left - the Lord's Supper.

Opposite this - Jesus blesses Mary Magdalene.

The head in the middle of the dark red-brown is highlighted in a muted olive green - alive or dead?

1958: Jesus am Ölberg / Kreuztragung

Two ceramics that Ursula Dethleffs called material pictures because she worked with different types of ceramics. We summarize these works as ceramics.

"Jesus on the Mount of Olives": It is night, the sky is almost black. A few dark blue indentations loosen up the image above the Mount of Olives. In the foreground, Jesus crouches praying, wrapped in a yellow robe - his face is covered with his hands. Above right his disciples: fearfully they nestle close to one another. They make it seem like they want to protect him - despite their fear.

The picture shows the loneliness of Jesus, who seeks closeness to God, his Father. At the same time, it becomes noticeable how great the disciples' fear of the Roman and Jewish rulers was.

“Carrying the Cross”: Little is known that at the crucifixion the carrying of the cross was imposed on two people in blue robes: Above, carrying the cross with his left arm, Simon of Cyrene, who was picked up by Roman soldiers, the condemned Jesus carrying the To help cross. Below, Jesus himself carrying the cross only symbolically. His figure is divided into two parts: an arm of the cross separates the small head with the crown of thorns from Jesus, his large body - wrapped in blue cloth - crawls on hands and knees up to the place of Golgata - depressed by the brutal judgment of the threatening crucifixion. Rust-red clay lies in front of him, as a symbol that his blood is shed here for all people.

There was no other artist from whom Ursula Dethleffs could have learned the steps of drying, firing and glazing to produce her works of art from ceramics; she was the first.

The technology is so difficult to master that it has probably remained the only one. After many years of experimentation with her potter, Ursula was able to afford a large special furnace with an extremely variable temperature range - thanks to the support of her parents. The relatively small number of successfully fired ceramics can no longer be determined. On our homepage are exhibited:

There was no other artist from whom Ursula Dethleffs could have learned the steps of drying, firing and glazing to produce her works of art from ceramics; she was the first.

The technology is so difficult to master that it has probably remained the only one. After many years of experimentation with her potter, Ursula was able to afford a large special furnace with an extremely variable temperature range - thanks to the support of her parents. The relatively small number of successfully fired ceramics can no longer be determined. On our homepage are exhibited:

see - Link in our homepage to the chapter:

Dethleffs works: number of works according to technique

ceramic | Plate mug | 38 |

| Fig. | 56 |

| Relief | 355 |

| Sculpture | 41 |

1972: Three church windows by Ursula Dethleffs in the Nikolaikirche (1288) in Isny

Ursula Dethleffs designed the three large rear glass windows for the Protestant Nikolai Church. The pastors and the parish council had chosen the topics: Tower of Babel, Pentecost, Holy Jerusalem. At the inauguration in 1972, Dieter W. Kohler interpreted the windows. At the Pentecost window in the middle he explained:

“Ursula Dethleffs depicts the joy of the outpouring of the Holy Spirit in the form of colored drops. The roar of the wind appears in the form of the sweeping, wave-like shapes in powerful, bright colors. They should be an expression of this: where God's spirit is, there is freedom. Freedom to set out to build the heavenly city, the heavenly Jerusalem from below. "

The texts for all three windows by Johanna Schanbacher can be found on our homepage with the link: Works in Public Collections:

1988: INRI

At the end of her life, Ursula returned to her earliest technique, albeit on a higher level. In the beginning she had playfully looked for mussels, snail shells, bird feathers etc. and then combined them into small works of art in an imaginative way.

As she got older, she transformed her frugality into a desire not just to throw away the old, but to bring it back to life. Object art does not depend on the superficial consideration of the individual parts such as a shell or a bird's feather. She takes a step back and transforms wood, string and boards into a Christian cross. The motivation is no longer playing with things, and no longer thrift, but the new goal of using artistic creativity to transform the old worthless into completely new values

The wooden cross is a simple example because it can tell so much about artistic creativity. Wood, a single tool and string are enough for a long time to say much more about the Christian faith with this wooden cross than with many words. Of course, the viewer is expected to deal with the work.

The Christian community today is composed of many different nations. Christianity shapes the common ground from the different. It's not about pomp, it's all about sticking together. This is often not easy - even a cord can break. This shows how at risk Christians are if they remain unaware of their humanity.

The Christian spirit was poverty, it was the desire for justice and help for the helpless.

Ursula Dethleffs has returned to her roots with her art. She looked at the objects with wide eyes again and understood what this art can do for people today

1989: resurrection

What is the essence here? The coffin open at the top? The orderly skeleton? The grave goods?

A girl asked her mother when she came back from school: how am I supposed to find you and papa in heaven later when everyone who has already died is jumping around as skeleton up there? Mama replied: Everyone up there has a cell phone. When you go to heaven, I will find out and I can call you. We'll meet at the meeting point. Then we're back together. It will be nice!

This concentration on the essentials is what object art demands.

At the first exhibition after Ursula's death, a clever speaker said regretfully: It's a shame - there are so many wonderful works by Ursula. But object art should be put in the desert.

He hadn't noticed that he only saw the old wood, the old cord, the rusted metal. He did not understand what Ursula Dethleffs said with every single piece of work. It's not always easy either. But it's worth investigating.

Bernd Riedle April 2021